1922 - First Leading Role

The Toll of the Sea

The Toll of the Sea

At age 17, Wong landed on her first leading role in one of the first Technicolor movies - The Toll of the Sea. The story is loosely based on Madame Butterfly, except the tragic Asian female character is Chinese this time.

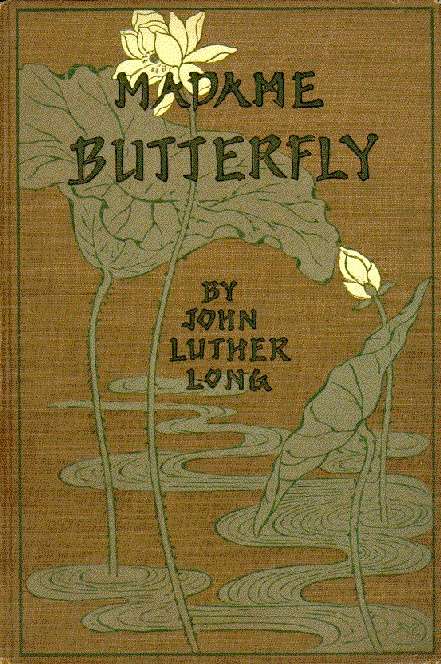

1929 - Last Silent Film

Piccadilly

Piccadilly

Wong made her last silent film, Piccadilly, the first of five English films in which she had a starring role. The film caused a sensation in the UK. Gilda Gray was the top-billed actress, but Variety commented that Wong "outshines the star" and that "from the moment Miss Wong dances in the kitchen's rear, she steals 'Piccadilly' from Miss Gray." Though the film presented Wong in her most sensual role in a British film, once again she was not permitted to kiss her Caucasian love interest and a controversial planned scene involving a kiss was cut before the film was released.

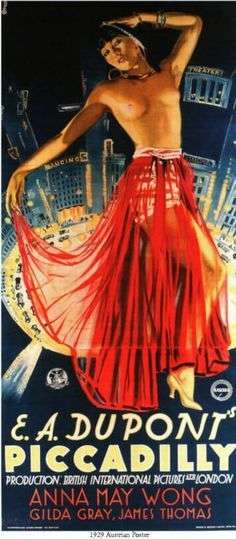

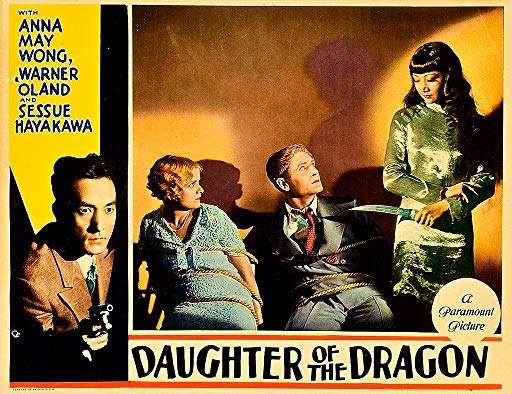

1931 - Bow Down to Stereotypes But Stunning Still

Daughter of the Dragon

Daughter of the Dragon

With the promise of appearing in a Josef von Sternberg film, Wong accepted another stereotypical role – the title character of Fu Manchu's vengeful daughter in Daughter of the Dragon (1931). This was the last stereotypically "evil Chinese" role Wong played. and also her one starring appearance alongside the only other well-known Asian actor of the era, Sessue Hayakawa.

Though she was given the starring role, this status was not reflected in her paycheck: she was paid $6,000, while Hayakawa received $10,000 and Warner Oland, who is only in the film for 23 minutes, was paid $12,000.

Though she was given the starring role, this status was not reflected in her paycheck: she was paid $6,000, while Hayakawa received $10,000 and Warner Oland, who is only in the film for 23 minutes, was paid $12,000.

Wong plays princess Ling Moy, an acclaimed dancer

1932 - Stardom & Digrace

Shanghai Express

Shanghai Express

Wong appeared alongside Marlene Dietrich as a self-sacrificing but vengeful courtesan in Sternberg's Shanghai Express. Her sexually charged scenes with Dietrich have been noted by many commentators and fed rumors about the relationship between the two stars. Though contemporary reviews focused on Dietrich's acting and Sternberg's direction, film historians today judge that Wong's performance upstaged that of Dietrich.

The Chinese press had long given Wong's career very mixed reviews, and were less than favorable to her performance in Shanghai Express. A Chinese newspaper ran the headline: "Paramount Utilizes Anna May Wong to Produce Picture to Disgrace China" and continued, "Although she is deficient in artistic portrayal, she has done more than enough to disgrace the Chinese race." Critics in China believed that Wong's on-screen sexuality spread negative stereotypes of Chinese women.

The Chinese press had long given Wong's career very mixed reviews, and were less than favorable to her performance in Shanghai Express. A Chinese newspaper ran the headline: "Paramount Utilizes Anna May Wong to Produce Picture to Disgrace China" and continued, "Although she is deficient in artistic portrayal, she has done more than enough to disgrace the Chinese race." Critics in China believed that Wong's on-screen sexuality spread negative stereotypes of Chinese women.

1930s - 1940s Things Are Wrong

Sino-Japanese War + Chinese Civil War

Sino-Japanese War + Chinese Civil War

Wong began using her newfound celebrity to make political statements: late in 1931, for example, she wrote a harsh criticism of the Mukden Incident and Japan's subsequent invasion of Manchuria. She also became more outspoken in her advocacy for Chinese American causes and for better film roles.

In a 1933 interview for Film Weekly entitled "I Protest", Wong criticized the negative stereotyping in Daughter of the Dragon, saying, "Why is it that the screen Chinese is always the villain? And so crude a villain – murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass! We are not like that. How could we be, with a civilization that is so many times older than the West?"

1935 - Are You Kidding Me

After her success in Europe and a prominent role in Shanghai Express, Wong's Hollywood career returned to its old pattern.

Because of the Hays Code's anti-miscegenation rules, she was passed over for the leading female role in The Son-Daughter in favor of Helen Hayes. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer deemed her "too Chinese to play a Chinese" in the film, and the Hays Office would not have allowed her to perform romantic scenes since the film's male lead, Ramón Novarro, was not Asian. Wong was scheduled to play the role of a mistress to a corrupt Chinese general in Frank Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), but the role went to Japanese actress Toshia Mori.

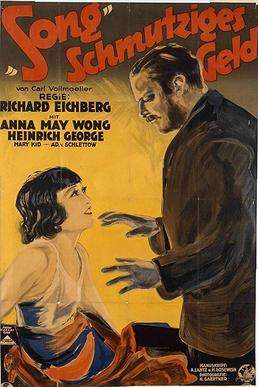

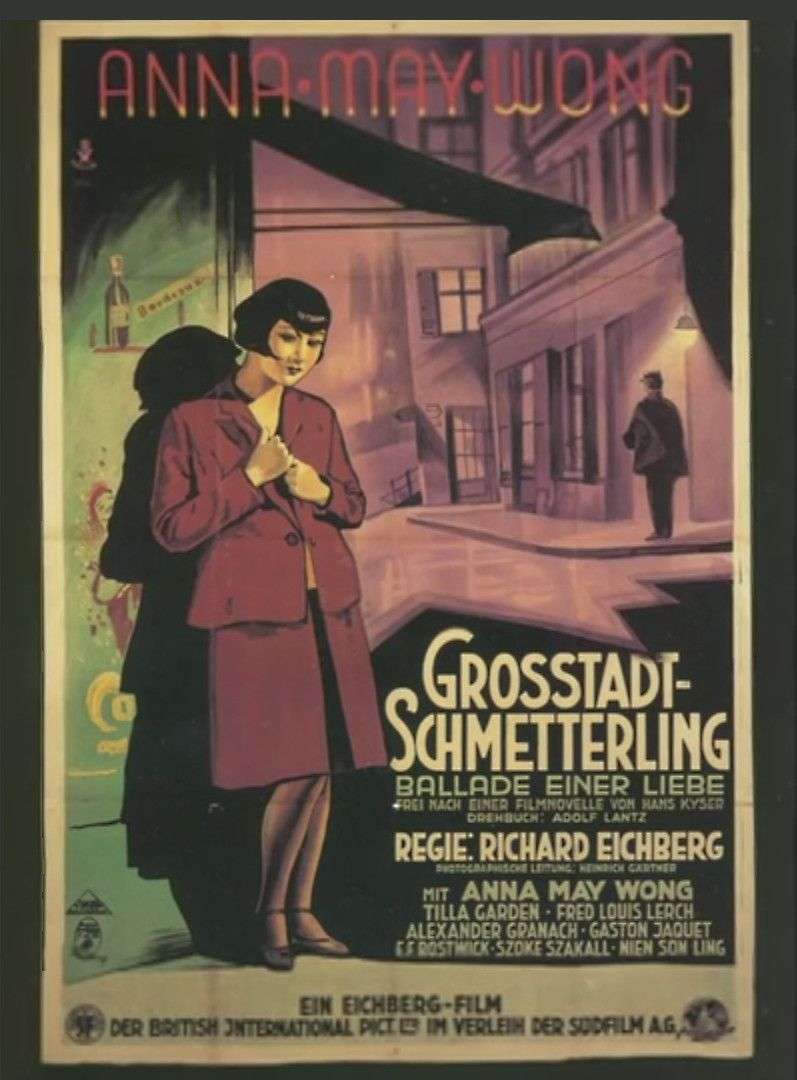

Again disappointed with Hollywood, Wong returned to Britain, where she stayed for nearly three years. In addition to appearing in four films, she toured Scotland and Ireland as part of a vaudeville show.

Because of the Hays Code's anti-miscegenation rules, she was passed over for the leading female role in The Son-Daughter in favor of Helen Hayes. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer deemed her "too Chinese to play a Chinese" in the film, and the Hays Office would not have allowed her to perform romantic scenes since the film's male lead, Ramón Novarro, was not Asian. Wong was scheduled to play the role of a mistress to a corrupt Chinese general in Frank Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), but the role went to Japanese actress Toshia Mori.

Again disappointed with Hollywood, Wong returned to Britain, where she stayed for nearly three years. In addition to appearing in four films, she toured Scotland and Ireland as part of a vaudeville show.

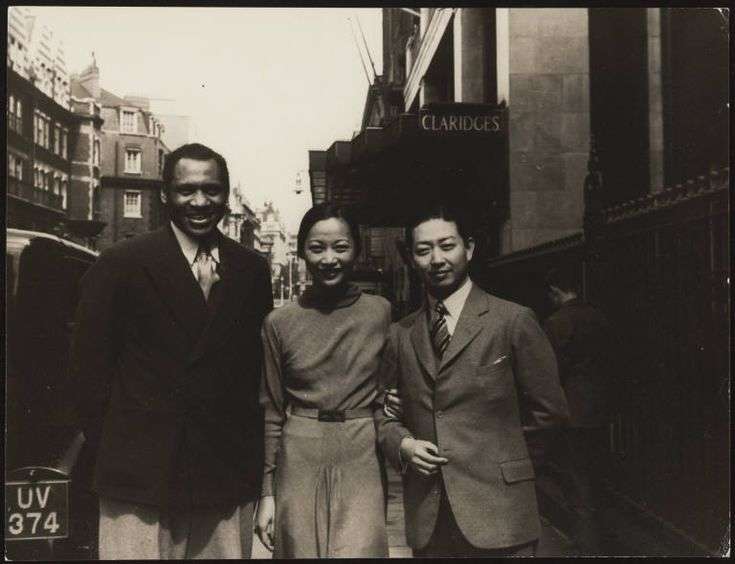

While in London, Wong met Mei Lanfang, one of the most famous stars of the Beijing Opera. She had long been interested in Chinese opera and Mei offered to instruct Wong if she ever visited China.

Anna May Wong with Paul Robeson and opera singer Mei Lan Fang standing in front of Claridge's, May, 1935. Photo by Fania Marinoff.

1936 - Visting China

During her travels in China, Wong continued to be strongly criticized by the Nationalist government and the film community. She had difficulty communicating in many areas of China because she was raised with the Taishan dialect rather than Mandarin. She later commented that some of the varieties of Chinese sounded "as strange to me as Gaelic. I thus had the strange experience of talking to my own people through an interpreter."

1937 - B Movies Are Better

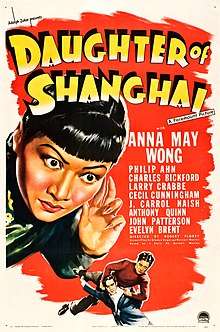

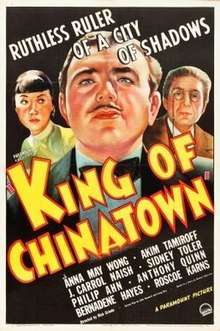

To complete her contract with Paramount Pictures, Wong made a string of B movies in the late 1930s.

Often dismissed by critics, the films gave Wong non-stereotypical roles that were publicized in the Chinese-American press for their positive images. These smaller-budgeted films could be bolder than the higher-profile releases and Wong used this to her advantage to portray successful, professional, Chinese-American characters. Competent and proud of their Chinese heritage, these roles worked against the prevailing U.S. film portrayals of Chinese Americans.

In contrast to the usual official Chinese condemnation of Wong's film roles, the Chinese consul to Los Angeles gave his approval to the final scripts of two of these films, Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939).

Later Wong starred in Bombs over Burma (1942) and Lady from Chungking (1942), both anti-Japanese propaganda and she donated her pay for both films to United China Relief.

Often dismissed by critics, the films gave Wong non-stereotypical roles that were publicized in the Chinese-American press for their positive images. These smaller-budgeted films could be bolder than the higher-profile releases and Wong used this to her advantage to portray successful, professional, Chinese-American characters. Competent and proud of their Chinese heritage, these roles worked against the prevailing U.S. film portrayals of Chinese Americans.

In contrast to the usual official Chinese condemnation of Wong's film roles, the Chinese consul to Los Angeles gave his approval to the final scripts of two of these films, Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939).

Later Wong starred in Bombs over Burma (1942) and Lady from Chungking (1942), both anti-Japanese propaganda and she donated her pay for both films to United China Relief.

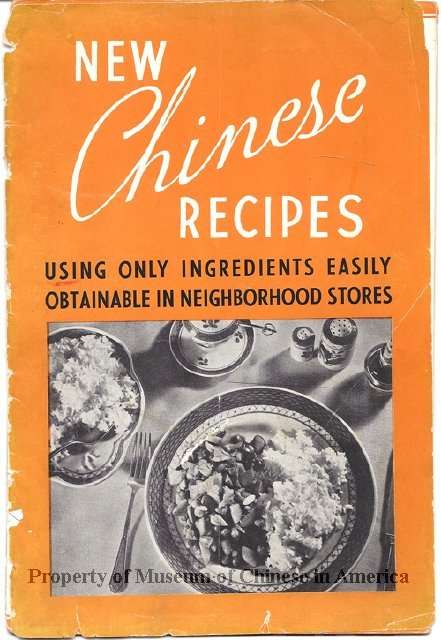

1942 - Cook Book

In 1942, Wong wrote a cookbook entitled New Chinese Recipes, one of the first Chinese cookbooks.

1950s - Her Own Show

She returned to the United States in the 1950s and became the first Asian American to lead a US television show for her work on The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong (her own name).

Wong's character was a dealer in Chinese art whose career involved her in detective work and international intrigue. The ten half-hour episodes aired during prime time, on Wednesdays at 9:00pm ET. Though there were plans for a second season, DuMont canceled the show in 1952.

Like most DuMont programs, no known copies of the show or the scripts are known to exist in any archive. The majority of the network's footage having been dumped into the Hudson River upon closure.

Episodes / Air Dates

1.

Wong's character was a dealer in Chinese art whose career involved her in detective work and international intrigue. The ten half-hour episodes aired during prime time, on Wednesdays at 9:00pm ET. Though there were plans for a second season, DuMont canceled the show in 1952.

Like most DuMont programs, no known copies of the show or the scripts are known to exist in any archive. The majority of the network's footage having been dumped into the Hudson River upon closure.

Episodes / Air Dates

1.

"The Egyptian Idols"

August 27, 1951

2.

"The Golden Women”

September 3, 1951

3.

"The Spreading Oak"

September 10, 1951

4.

"The Man with a Thousand Eyes"

September 17, 1951

5.

"Burning Sands"

September 24, 1951

6.

"Shadow of the Sun God"

October 1, 1951

7.

"The Tinder Box"

October 31, 1951

8.

"The House of Quiet Dignity"

November 7, 1951

9.

"Boomerang"

November 14, 1951

10.

1960 - Walk of Fame Star

For her contribution to the film industry, Anna May Wong received a star at 1708 Vine Street on the inauguration of the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

She is also depicted larger-than-life as one of the four supporting pillars of the "Gateway to Hollywood" sculpture located on the southeast corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, with the actresses Dolores del Río (Hispanic American), Dorothy Dandridge (African American), and Mae West (White American). Even though she put the first rivet in the Grauman's Chinese Theatre in the 1926, but she wasn't invited to leave prints in the cement. Her contribution to film was marked with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

She is also depicted larger-than-life as one of the four supporting pillars of the "Gateway to Hollywood" sculpture located on the southeast corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, with the actresses Dolores del Río (Hispanic American), Dorothy Dandridge (African American), and Mae West (White American). Even though she put the first rivet in the Grauman's Chinese Theatre in the 1926, but she wasn't invited to leave prints in the cement. Her contribution to film was marked with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

1961 - The End

On February 3, 1961, at the age of 56, Anna died of a heart attack as she slept at home in Santa Monica, two days after her final screen performance on television's The Barbara Stanwyck Show.